Gender, Sex, and Science in China

- zarondc

- Apr 16, 2019

- 2 min read

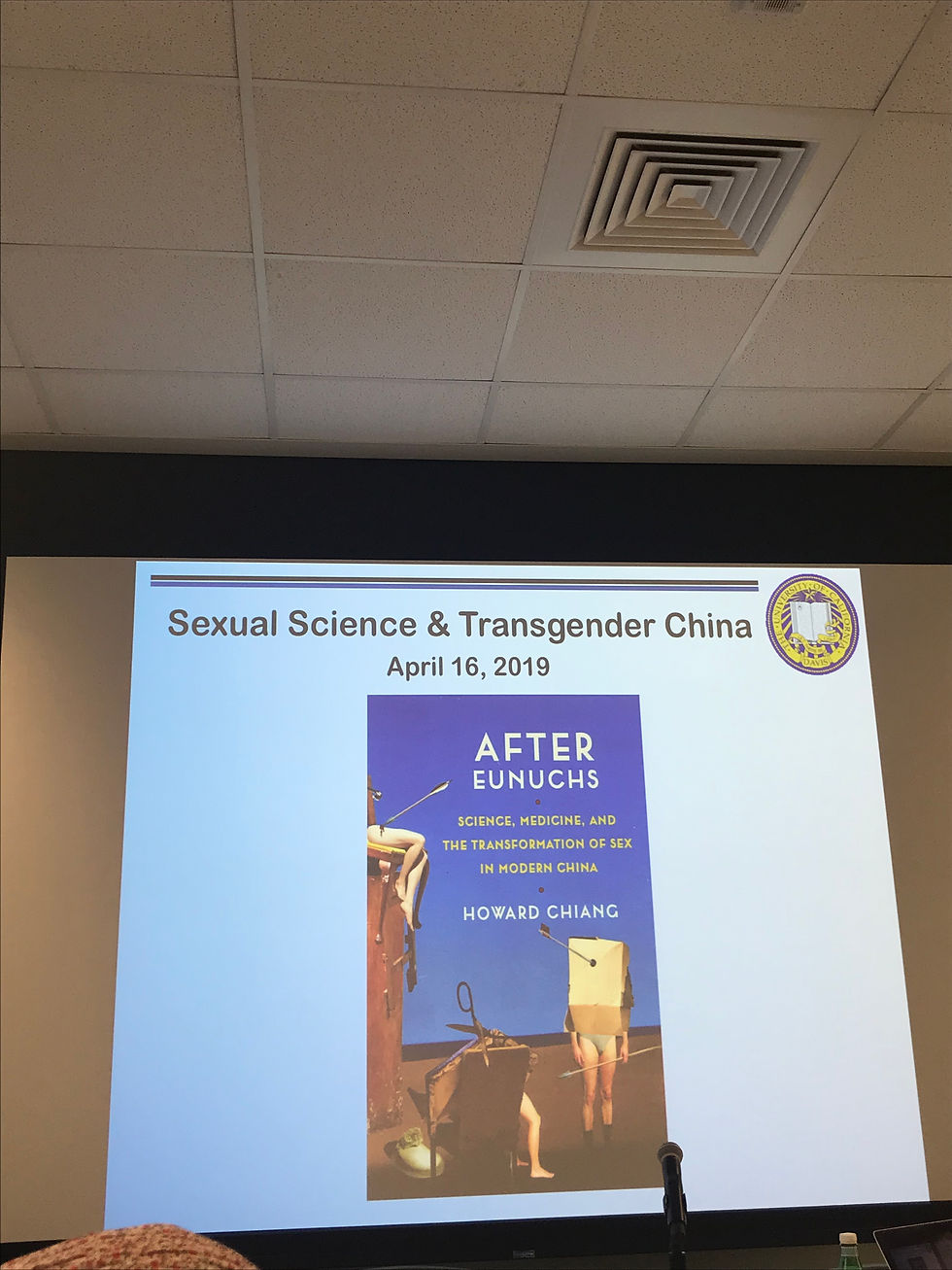

In coordination with Asian Studies program on American University's campus, tonight the academic Howard Chiang hosted a lecture on the evolution of sexual sciences in China as covered in his book After Eunuchs: Science, Medicine, and the Transformation of Sex in Modern China. Howard Chiang currently serves as the Assistant Professor on the Department of History at UC Davis in California. Chiang has authored upwards of 11 works centering around the study of the intersection of queer gender and sexuality with medicine and science within China, with an emphasis on their historical trajectory. The focus of Chiang's talk was the evolution of transgender between the periods of the late 19th to mid-20th centuries.

Chiang began the discussion on the transformation of sexology in China by tracing a similar linguistic phenomena of the word Xing. Like the eventual change of the word's meaning, concepts of sex likewise mutated across the passage of time. Beginning during the times of the Opium Wars China experienced greater Western influence, with new in-depth anatomical designs reworking the pre-existing notions surrounding the human body. Chiang notes that the decline of eunuchs, castrated government officials, was a signal of a shift in society. As medicine and medical photography exposed the body more so than ever before, practices such as castration appeared as something "wrong" in light of it. The discovery in the 1930s that all people possessed both "male" and "female" genes brought the mutability of sex to the forefront and made people rethink the idea that sex-change was a biological impossibility.

International sensations such as Christine Jorgenson, the first transgender woman to receive sex reassignment surgery in America spread eastward during the 1950s, with Xie Jianshun being dubbed the "Chinese Christine". Both were soldiers who underwent medical procedure to reconfigure their sex and, instead of being vilified, were often considered sympathetically by popular society and as a sign of medical advancement.

Chiang finished his time by moving outside the realm of sexology to discuss the greater Sinephone, or "Chinese speaking", world and the need for academia to abandon the Eurocentrism that has dominated it for centuries. Although the introduction of transgender science in China could be considered the adoption of Western medicine and mentalities, could it not also have been a refinement of existing understanding of transgender concepts in China? Either way, Chiang struck a chord in the audience in exposing the way in which we mark historical progress through a Western set of standards.

Comments